- Home

- Michel Tremblay

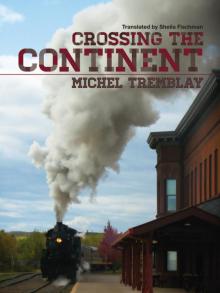

Crossing the Continent

Crossing the Continent Read online

This is a work of fiction. The names of some characters are real, but everything else is made up.

– M. T.

For Lise Bergevin, who has been asking me for ages for a novel about Nana’s childhood

Him do I hate even as the gates of hell who says one thing while he hides another in his heart.

– Homer

The Iliad, translated by Samuel Butler, 1898

To write is to make the dead rise from their graves and to pull them along into the light.

– Robert Lalonde

Espèces en voie de disparition

Imagining something is better than remembering something.

– John Irving

The World According to Garp

1

The House

in the Middle

of Nowhere

They took shelter on the veranda that surrounds the house on three sides. Grandpa Méo had built it a few years ago, to keep them – Rhéauna, the eldest; Béa, who was younger; and Alice, the youngest – from getting lost in the endless fields that file past to the horizon, where it’s so easy to lose your way toward the end of summer when the corn is high. And for a promenade in the evening with his wife on his arm, without having to worry about the mud or the dust from the dirt road that leads to the main route. They cover ten times, twenty times the length of the wooden veranda from end to end and stop when Joséphine declares that she’s too tired to go on, when they both know that it’s Méo whose legs aren’t what they used to be. The neighbours think the addition to the house is useless and even more, pretentious, but if they’d known how much pleasure it gives Joséphine and Méo on their long walk every night they might change their opinion.

The two little girls are sitting on the top step of the big white-painted staircase, their knees squeezed together, and they’ve placed their precious paper bags between them. Alice is having her nap in their room and she will discover her surprise bag on her pillow when she wakes up. The girls suspect that it won’t be much of a surprise today because money has been scarce for some time and the exotic fruits – oranges, for instance, or the legendary pineapples they had tasted, howling with happiness, a few years before – have disappeared from the Sunday afternoon menus with no hope that they will come back. Grandma Joséphine had practically apologized when she took the three tiny bags from the cupboard where she’d hidden them. But the two girls had laid on their enthusiasm a little too thickly and Grandma seemed satisfied. No one was fooled, but their Sunday afternoon was saved from monotony.

Before opening them, they try to guess what might be inside the two brown paper bags.

Béa scratches her knee where a mosquito bite is blooming into a big red spot that’s been causing her a good deal of pain since morning because she’s been scratching it so much. A vicious circle that has been driving them all crazy since the beginning of summer. Although Grandma has been telling them not to scratch, that it will be gone in half an hour if they tough it out, but they can’t help themselves, especially Grandpa who all his life has sported the most spectacular and nastiest sores. So they scratch their itches with their fingernails, emitting long sighs of relief, even if it means that a few minutes later it will all begin again, worse than before. Even Grandma doesn’t follow her own advice: she complains a little too often about how her arthritis is so painful that she has to massage her bones, her excuse for scratching herself … Her three granddaughters and her husband laugh a little and she tells them, with a shrug and a smile of bad faith at the corners of her lips, that they can’t imagine how painful arthritis is. Meanwhile, Béa’s knee is a pitiful sight and Rhéauna expects a crying jag before the day is over. Béa is more lethargic, but for some unknown reason, not so patient than the rest of them.

“Anyway, it can’t be candy, the bag doesn’t weigh enough.”

Rhéauna shrugs.

“I don’t care what it is as long as it’s something to eat.”

Béa lets out that laugh of hers that so often sends flocks of crows up from the fields. This time it’s a rabbit that scampers off, ears flat, muzzle quivering.

“Don’t worry, we can eat it. Grandma knows us.”

Her sister hefts the bag again.

“Could be, but I don’t think it’s very filling … It hardly weighs a thing!”

On that she’s mistaken. Béa is the first to open her bag, as usual, and is instantly ecstatic.

“Peanuts in the shell! We haven’t had those for ages!”

Grandma had found a huge bag of peanuts in the shell on display out front of the general store the day before and, despite the exorbitant price, thought she’d make the children happy by purchasing a handful for their Sunday afternoon snack. Peanuts are a rare commodity in Maria, Saskatchewan, in this year of the Lord 1913, and she wondered how the bag had ended up on Monsieur Connells’s steps. She knew that peanuts came from the southern United States, Georgia or the Carolinas, anyway, a good long train trip and, during her lifetime, she had seen them only rarely.

Béa thrusts her hand into her bag, takes out a peanut and pops it open with her thumb and forefinger.

“Just think, Grandma pretended she was sorry when she gave it to us. She really got us. What a surprise!”

Rhéauna’s mouth is already full.

“It’s so good, it’s so good, it’s yummy!”

Béa taps her arm.

“Don’t talk with your mouth full.”

“Look who’s talking! You could’ve waited to swallow before you said that.”

The next few minutes are pure delight. Happy, they laugh, bodies offered to the sun, mouths full of the sweetish taste of the peanuts which they chewed for as long as possible before they swallowed. To make it last.

The last peanut is gone and Rhéauna looks at her sister who hasn’t finished masticating.

“You fixed it so you’d finish after me!”

Béa gives her a big smile.

“Grandma says so all the time, Nana. You eat too fast.”

It’s true. She likes to eat and when her plate arrives she has trouble containing herself: all those wonderful things to eat, often fatty because they don’t skimp on butter in the house, they attract her and she’s not satisfied until she fills her mouth, emphasizing the pleasure she feels at the combination of tastes with little exclamations of bliss that amuse the rest of the family. Especially eight-year-old Alice who thinks that she’s the funniest thing on earth with her clucks like an excited turkey and her sighs of contentment.

“And Grandma always says you make everybody wait because you don’t eat fast enough.”

Which is also true. It sometimes seems that Béa deliberately chews for too long as if to test the family’s patience. But she claims it’s because she likes to swallow her food after she’s extracted all the juice, and they’ve decided to believe her.

But Rhéauna doesn’t think she’s been beaten. She takes a peanut shell from her bag, rubs it a little with her forefinger to remove the stiff little hairs attached to it and pops it in her mouth. She knows that Béa is too scornful to take up the challenge, ensuring herself of an easy victory that’s still fairly agreeable. So she starts to chew with little murmurs of appreciation as if she’d just put a delicious candy in her mouth, one of the ones she and Béa liked best, a honeymoon or a peppermint heart.

“Anyway, you can’t boast about winning today! It’s my turn, I’m going to finish way after you!”

Béa gapes at her for several long seconds before replying:

“You’d have to give me a brand-new dollar with the King of England’s picture on it to make me eat that and I wouldn’t eat it. It doesn’t count, you’ll find out when you eat things you aren’t supposed to. You’re

cheating, Nana. What’s in your mouth isn’t even real food!”

Rhéauna goes on with her painful mastication. It tastes terrible. Like a rough piece of wood with no juice. It breaks between her teeth with an unpleasant sound instead of soaking with saliva, it scrapes her tongue, it sticks to the roof of her mouth and she’ll have to chew for hours before she can swallow it. And she’s not sure that she can … Also, it doesn’t even taste like peanuts, it tastes like the bark of a tree. Just the thought that she is chewing a piece of bark turns her stomach. Only pride keeps her from spitting it to the bottom of the steps, where the ants would be thrilled with the unexpected feast. The girls have discovered any number of spat-out candies crawling with ants that try to dissect and then transport them to their nest. In fact, one of their sister Alice’s favourite games is to find what she calls “alive candies,” then sit and watch the nervous little bugs, studying them for hours without tiring.

Meanwhile, Béa turns away, pinching her nose.

“If you’re going to throw up, smarty-pants, go do it inside the house. I don’t feel like having Grandma make me help you clean up your mess!”

But there’s no question of Rhéauna losing face. Béa won’t have the satisfaction of seeing her grimace as she spits out the pulp of wet peanut shell. So she persists, chews, swallows the bit of liquid that tastes like the devil, without flinching, sitting stiffly on the top step, maybe staring a little but with forehead high and heart pounding: she has just asked herself what would happen if by bad luck peanut shells turned out to be poisonous.

Because it often happens that the two of them are like communicating vessels, always thinking the same things at the same time even though they aren’t twins, Rhéauna is not surprised when her sister says barely a few seconds after the thought had crossed her mind:

“I think I read somewhere that peanut shells are poisonous.”

Rhéauna smiles despite the more and more disgusting taste that fills her mouth.

“If you’re trying to scare me you’re wasting your time.”

“I just said it so you’ll know.”

“Yeah, sure …”

“Sometimes it’s even fatal.”

“If it were fatal you’d have stopped me before I put it in my mouth, Béa. You’re my sister.”

Béa moves very close to her. Rhéauna can smell peanuts on her breath, an odour so wonderful it makes her want to spit out the horror that she’s masticating.

“Who says I’d’ve stopped you from eating your shell even if I knew it was fatal?”

“Come on, Béa, you wouldn’t have let me die …”

“Oh, no? That’s what you think.”

Tears, fat and generous and numerous, are there before Rhéauna can hold them back. A few seconds later, they’ve wet her face and neck. Béa also possesses the loathsome power to always come up with the words that will burn, aiming every time at the place that hurts most, and she’s happy to use it on the whole family, her grandparents as much as her two sisters. It’s not spiteful, it’s her way of defending herself and everyone knows it; Grandma Joséphine has explained it more than once. But it’s painful and it’s sometimes hard to forgive her for what she’s said. Afterward, of course, she claims she didn’t mean it …

Rhéauna knows very well that Béa would never let her die, not poisoned by a peanut shell or any other way, but the mere thought that she can actually claim the opposite so she’ll think that she hasn’t lost the ridiculous bet overwhelms her though she doesn’t know why, and she realizes that she can’t hold back the goddamn tears that must delight Béa, despite the impassive face she shows.

She wipes her eyes, her cheeks, her neck on the sleeve of her crushed cherry-red dress that she likes so much. Even that is going to be ruined!

“Nana, your dress is going to be covered with snot.”

Rhéauna is on her feet in less than a second and she points to her sister after spitting out what she had in her mouth, the better to enunciate:

“You’re taking revenge, aren’t you? You’re taking revenge because for once I won! You’re always like that! You can’t accept not winning. You always have to put in your two cents’ worth or else you make us pay for not letting you have your way. Have you any idea how bad what I put in my mouth was? You could’ve let me win for once! It doesn’t cost much to make people happy once in a while.”

Without wasting a second, and apparently to defy her sister, Béa pounces on her own bag of peanut shells, takes a handful, stuffs it in her mouth and starts to chew. Now she’s the one talking with her mouth full.

“You can cry all night, Nana, but you still won’t win!”

Rhéauna watches her chew for a good moment before she replies.

“Maybe peanut shells aren’t poisonous but I hope you choke on them!”

She leans toward her sister. Their noses nearly touch.

“Can you imagine what it’s like to choke on a handful of little pieces of dry wood that won’t go down when you try to swallow them! Eh? It sticks in your throat, you can’t breathe, you turn really bright red, your eyes pop out of your head, your tongue gets thick and then you haven’t got any more breath and you die, with a death rattle like a poisoned rat!”

Béa is already spitting out the peanut shells, then she raises her head, a nasty smile on her lips.

“Anyway I still won!”

Supper was tinged with a glumness that surprised Joséphine.

Usually there’s no lack of subjects for conversation around the table – three little girls aged eight, nine and ten have things to say – but that night she senses an animosity between the two older ones that she can’t explain. Something she didn’t witness must have happened that afternoon, and all her attempts to pierce the mystery of their serious expressions and furious looks are in vain. No doubt, it’s some trivial matter between two idle children trying to pick a quarrel, a fight over nothing. She’s used to settling some of those every week. This time, though, it’s going on, their foreheads stay creased, their mouths bitter, when usually Nana and Béa are reconciled over a generous helping of shepherd’s pie or beef stew. They both like to eat – even though Rhéauna is constantly denying the evidence – and usually a good hot meal can tone down their turbulent little-girls’ quarrels. They forget that a few hours earlier they were pulling the other’s hair and calling each other names and the conversation, made up of minor anecdotes from country schools or small-town rumours that can’t be checked, picks up where they’d left it at the meal before this.

Even Alice realizes that something is wrong. She swallows her stuffed cabbage while she watches her sisters, each one in turn, trying to figure out what could have happened between them for such a silence to fall over what is usually the liveliest meal of the day. They are the ones who usually make conversation and she drinks in their words, thinking to herself that she can’t wait to be as old as they are and have so many interesting things to say.

But less fearful than her grandmother, she gets right to the point:

“You aren’t talking very much.”

Béa lifts her nose from her plate.

“We aren’t talking at all, there’s a difference.”

“How come you aren’t talking at all?”

This time it’s Béa who replies. With her mouth full.

“Because we haven’t got anything to say! We aren’t like some people I know, we don’t talk when we’ve nothing to say …”

Joséphine allows herself to intervene because Béa is too unfair. Alice is the quietest member of the family and no one can accuse her of being a chatterbox.

“Béa, don’t accuse your sister of what you deserve to be blamed for! And I’ve told you a thousand times, don’t talk with your mouth full!”

Now, for the first time in ages, since she was very little, in fact, when it was all she could come up with if she couldn’t think of anything to say, Béa sticks out her tongue at her grandmother, a tongue still covered with overcooked cabbage and greasy pork.

It’s ugly, it’s rude – everyone agrees, herself first – and a kind of indignant amazement falls over the dining-room table. Forks stay frozen between plates and mouths, Grandma’s shoulders are shuddering and Grandpa, who usually hears nothing and sees nothing at the table because women’s conversations bore him, shoots a look filled with such anger that Béa swallows a mouthful that goes down the wrong way and she chokes.

Rhéauna leans over her.

“I told you you’d choke.”

Méo slaps the table, just once. The four women hunch their shoulders, dreading one of the rare but terrifying fits of rage by this overly patient man who has a hard time controlling himself when he gives in to anger. But he says nothing, merely gives Béa a filthy look.

“I’m sorry, Grandma. I won’t do it again.”

Joséphine wipes her face with her apron which she’d forgotten to remove before taking her place at the table.

“I don’t know what’s the matter with you two tonight but you’re scaring me …”

Méo gets up, walks around the table, leans over Béa and grabs her plate in an exaggerated gesture.

“If your grandmother’s food makes you stick your tongue out, you can do without.”

He takes the plate to the sink after pouring its contents into the garbage.

The meal is over. Stomachs are knotted, no one wants dessert, the table is cleared in seconds. Méo stands next to his wife, who is clearing the table.

“What’s got into them this time?”

She gives him a desperate look.

“Who knows? Maybe they can sense what’s coming …”

He puts his arm around her waist the way he used to, draws her toward him.

“Oh, come on. How would they know?”

“They can’t, Méo, but children sense things … They must feel that something’s coming. I can’t do it, Méo, I can’t do it.”

He kisses her behind the ear. That was how he’d seduced her forty years earlier when their country did not exist yet and they were nomads, he was in any case, looking for a place to settle. Before they were won over by the vast Saskatchewan prairies, the extravagant sunsets and the possibilities of tremendous harvests thanks to the rich and fertile soil. Before that small parcel of land in the middle of nowhere, in a landscape with no horizon that had always belonged to a people of whom they were the proud descendants and had finally come back to them. Before the house that Méo had built with his own hands for the sons his wife hadn’t given him because she’d had four daughters – Ernestine, Titite, Maria and Rose whom they never saw as a matter of fact because they were scattered all across the continent. The Desrosiers “diaspora.” Which is the only fancy word he knows – he found it in a newspaper article about Jews and Cajuns – and he often says it when he talks about his family.

Crossing the Continent

Crossing the Continent